The world’s oldest academy of engineering sciences

Sweden’s second youngest Royal Academy, the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), was founded as recently as 1919, but is nevertheless the world’s oldest engineering academy.

History doesn’t repeat itself. But when used correctly, it helps us to move forward.

100 years of technology in the service of humanity

The Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) came into being at a time when Sweden was facing challenges that are in many ways similar to those we see today. The First World War ended in 1918 after having crippled Europe for more than five years. There was an energy crisis. In many countries, the slow electrification of society had begun, but in Sweden industry was heavily dependent on coal, which was largely imported from abroad. The war was a period of major competition for coal, revealing how fragile the Swedish energy situation was. New energy solutions were needed, and an independent player was needed to drive technological advances. The issue was escalated all the way up to the Swedish Riksdag and on 24 October 1919, just under a year after the war had ended, King Gustav V cut the ribbon for IVA’s premises on Grev Turegatan in Stockholm. And so the world’s first academy of engineering sciences was born. The initiative was backed by Axel F Enström, the then head of the industrial office at the National Board of Trade Sweden, and he became the Academy’s first President.

A place for research and progress

IVA rapidly developed into an important arena for researchers and other stakeholders who wanted to work together in order, as the statute put it: “to further technical-scientific research and thereby promote Swedish industry and the utilisation of the country’s natural resources”. The initial focus was very much on the energy issue. But the Academy attracted members in many different areas of expertise, all of which were considered important in tackling the future societal challenges facing Sweden.

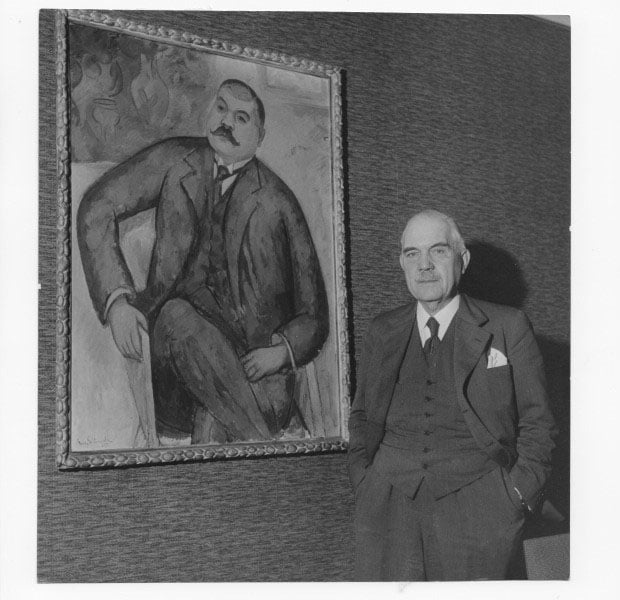

As an example, Hjalmar Sjögren, a renowned professor in mineralogy and geology, donated, through his wife Anna Nobel, a valuable library to IVA to be used as a resource for research and education. The donation comprised of about 10 000 volumes of books, reprints, maps, and manuscripts. Out the total of about 3600 book titles in the Sjögren Library almost 600 can be considered of importance. About 100 of these books are particularly rare and/or valuable often reporting early advances in the basic sciences and astronomy.

Learn more about the Sjögren Library.

Originally, the Fellows of IVA were split into seven Divisions, focusing on everything from chemical engineering and electronics to mechanics and shipbuilding.

In the early 1920s, IVA moved from simply promoting technical research to also beginning to conduct such research on its own premises. The Academy opened its first laboratory in the basement in 1923, and several more soon followed. During the inter-war years, research was conducted on everything from concrete and cement to electric heating and more efficient ways of producing charcoal.

Sweden’s first start-up hub

By the late 1930s, IVA’s research activities had grown so much that the Academy was forced to move them into larger premises. The opportunity arose for the Academy to build its own “research station” at the National Swedish Authority for Testing, Inspection and Metrology, next to KTH Royal Institute of Technology. Small and medium-sized research teams began moving into the much more spacious premises, giving them access to laboratory technology that was otherwise only available at universities and large companies. Technical research was conducted along with testing of practical applications spun off from the advances being made. The operation, which opened its doors in 1943, was later identified as perhaps Sweden’s first incubator for new technology companies. The more spacious premises also offered opportunities to broaden research activities. Research topics began to include safer traffic solutions and new technical solutions to make modern homes more efficient. In the shadow of the Second World War, the Swedish Defence Research Agency was also starting to conduct advanced experiments in the emerging field of nuclear power. Sweden’s first nuclear reactor was built in a cavern 25 metres below ground and was inaugurated in 1954. IVA continued to run its research facility until January 1969, when responsibility for the operation was handed over to other actors.

The economic sciences enter the picture

IVA’s ties with industry and the business community were strong from the outset, and they were further reinforced when IVA set up the Business Executives Council comprising Swedish companies and public enterprises. Over the years, more and more links were also forged with the economic sciences. After many years of discussion on establishing a separate “Academy of Economics”, in the late 1980s the IVA Presidium decided to incorporate this field of research into its own operations. With this change in course, the Academy rephrased its overarching purpose to read: “promoting technical and economic sciences and the development of the business community”.

Over the years, IVA’s international engagement also grew. In 1981, the decision was taken to set up the system of Swedish Science Attachés. The initiative, now part of the Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis, involved IVA placing employees in embassies around the world. Their task was to monitor and report back on technological developments in the various countries.

Continued focus on future challenges

Over the years, IVA’s operations have continued to grow and develop. As societal challenges and opportunities have evolved, the Academy has repeatedly expanded its field of work into new spheres of knowledge – biotechnology, digitalisation, nanotechnology and cybersecurity to name but a few. Today, the Academy consists of nearly 1,300 Fellows of IVA divided into 12 Divisions and a Business Executives Council with members from 250 companies and organisations. IVA remains an important meeting place where research, business and politics come together. Our mission is still to deliver science-based knowledge that can contribute to sustainable social development. And the future of our energy supply, where our story began over 100 years ago, remains high on our agenda.